Στις αντιδικίες για την επιμέλεια, οι μητέρες και τα παιδιά που καταγγέλλουν ενδοοικογενειακή βία και σεξουαλική κακοποίηση αντιμετωπίζονται με δυσπιστία. Δικαστές, δικηγόροι, τεχνικοί σύμβουλοι και σύμβουλοι ψυχικής υγείας χωρίς κατάρτιση σε θέματα παιδικής κακοποίησης και ενδοοικογενειακής βίας, πολύ συχνά απορρίπτουν ως ψευδείς τις κατηγορίες ενδοοικογενειακής βίας – ακόμα και όταν υπάρχουν πολύ σοβαρές ενδείξεις – και τις αποδίδουν στη γονική αποξένωση. Το αποτέλεσμα είναι η δευτερογενής θυματοποίηση τόσο των παιδιών που εξαναγκάζονται σε επικοινωνία με τους κακοποιητές τους όσο και των προστατευτικών γονέων που παρακολουθούν ανήμποροι την κακοποίηση των παιδιών τους καθώς παλεύουν με τη Δικαιοσύνη.

Πρωτότυπο κείμενο:

As a special consultant to Colorado’s child welfare agency, Susan Coykendall accepted that there was no reliable profile for a child abuser, but she was fairly certain Bruce was not one.

She came away from their first meeting in 2015 with the impression that he was a bit absent-minded and hapless but not a danger to his then-infant son. She described him as having a “Peter Pan”-like quality.

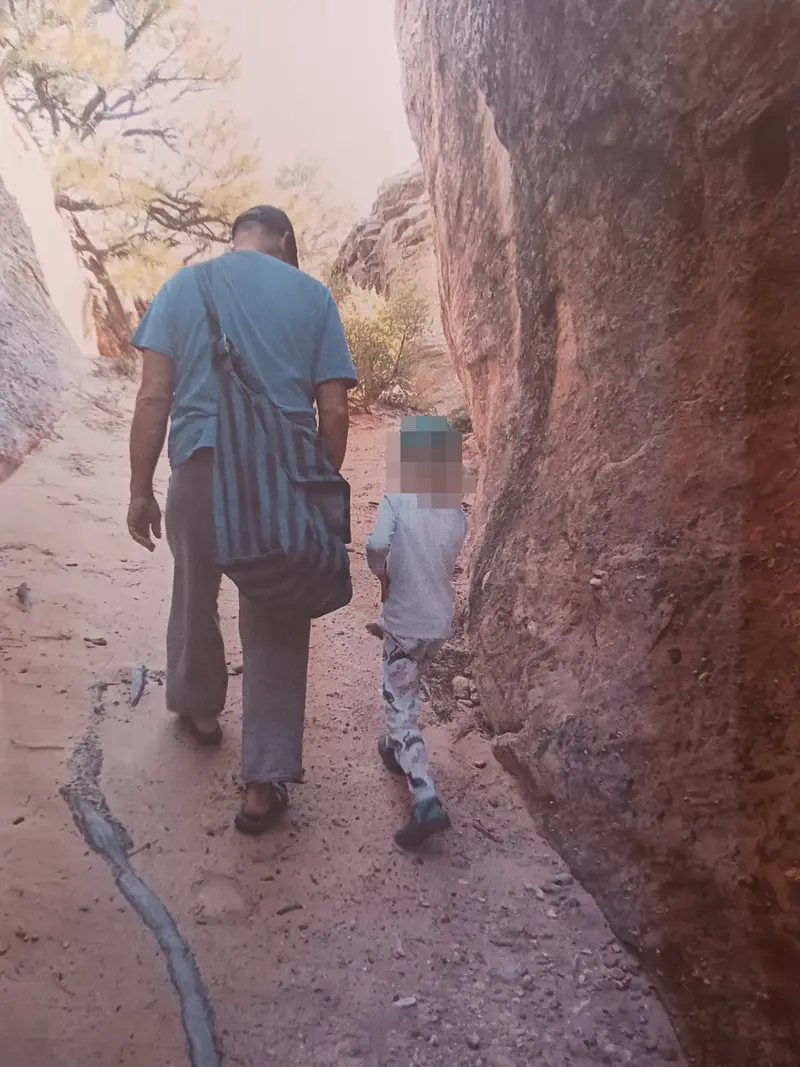

Coykendall was assisting Colorado’s Department of Human Services evaluate Bruce after the child returned from visiting him with a “black and blue mark on his forehead,” according to child welfare records. The injuries and domestic violence had been reported by Christine, Bruce’s then-wife and the boy’s mother. (ProPublica is not using the parents’ full names to protect the identity of the child.)

Christine told a caseworker she did not want an investigation for fear it would escalate the situation. Nonetheless, authorities investigated and found no evidence that Bruce “would hurt his son.” But because of the seriousness of the claims, DHS requested Coykendall provide her professional opinion.

While Coykendall was conducting her assessment, DHS received a second report from the infant’s pediatrician. The 19-month-old had returned from a visit with his father with “irritated” genitals reported by his mother and lumps on his head, the physician said, according to child welfare records. The agency did not investigate, stating it did not meet the legal standard for abuse or neglect.

Bruce, who goes by a nickname, denies ever physically or sexually abusing his son. He did admit to roughhousing with him, which may have sometimes led to injuries. “If [he] got a bump or a bruise, he’s just being a boy. … My son is a boy through and through. … He’s beggin’ for the roughhouse.”

If [the child] got a bump or a bruise, he’s just being a boy. I mean, unfortunately, there’s a vast difference between how boys play and how girls play, and my son is a boy through and through.

I mean, today, he got pissed off at me and he fucking was throwing punches at me and whaling on me. And he like, and he’ll be like, “I bet you can’t tickle me now.” He’s beggin’ for the roughhouse.

Bruce

Father

Speaking to reporter Hannah Dreyfus

Coykendall said she does not recall hearing about the second report to child welfare officials. Nor did she know Bruce had been charged with third-degree assault years prior for injuring a co-worker at an auto repair shop, according to police reports. (Bruce said he was trying to break up a fight. The charge was reduced to harassment through a deal to which Bruce pleaded no contest.)

But she did learn that during the initial investigation Bruce spontaneously confessed to police officers, court officials and child welfare investigators that decades earlier, at age 16, he had sexually assaulted a 4-year-old girl. According to police reports, Bruce said he performed a sex act on the child while babysitting her on a joint family vacation in the Poconos. (Colorado police did not open a case because the incident had taken place outside their jurisdiction.)

“There was no victim in that situation except myself,” Bruce told me. “That alleged victim did not suffer and had no recollection of it. But I beat myself up for decades thinking that I was fucked up, right? The silver lining being I finally told everybody. And everybody said: ‘Dude, you were young and stupid and pubescent. … Don’t beat yourself up about that.’”

The admission gave Coykendall pause, she later recalled. “I take things like that very, very seriously.” But his candor and explanation — he was intoxicated — allayed her concerns. She concluded “it was not a part of his adult repertoire of behavior. … It was an anomaly.”

“This is gonna sound ridiculous, but I’m — what I call the creep-o-meter,” Coykendall told me when we first spoke months ago. “Like he was so far down at the bottom of it that it wasn’t even, it wasn’t a concern, once I understood how it had happened and what all the circumstances were.”

This is gonna sound ridiculous, but I’m — what I call the creep-o-meter. It’s kind of my own personal thing. Like he was so far down at the bottom of it…

…that it wasn’t even, it wasn’t a concern, once I understood how it had happened and what all the circumstances were.

Susan Coykendall

Special consultant to Colorado’s child welfare agency

Speaking to Dreyfus

In her psychological evaluation, Coykendall said her interactions with Bruce “raised no red flags.”

Coykendall had so few concerns about Bruce that she initially offered to skip writing a report to save the child welfare office the money. Jennie Thomas, the lead child welfare investigator on the case whom Bruce said he knew personally, recommended he pay for a report and use it as evidence that he was a fit parent. “I suspect Christine plans to try to use a custody case to keep” their son away from Bruce, Thomas wrote in a Sept. 21, 2015, email to Coykendall, which was later included in court documents. “It might be smart for him to have something substantiating that she is wrong about him.” Coykendall agreed, and Bruce paid her for the report. (Thomas said she had no personal connection to Bruce prior to meeting him in her capacity as a child welfare caseworker.)

Seven years after Coykendall penned the report about Bruce, I called to ask her recollection of him. I wanted to hear from an expert who was familiar with this case and had dispassionately weighed the contradictory accounts that I was now struggling to reconcile. I told her that for years following her evaluation, doctors, psychologists, school officials and even a dental worker had contacted DHS with concerns that Bruce might be abusing his son. Over 36 reports of potential abuse were made to Colorado child welfare officials by more than a dozen professionals who are considered mandatory reporters, according to court and child welfare documents. Of the five who agreed to speak to me, none said they knew that others had made similar reports.

I kept grappling with a foundational question: How could so many adults in the child’s life believe he was being abused and report those concerns to authorities while others who saw the same reports came away believing it wasn’t possible? Some in the latter group would point to the boy’s mother as the source of the allegations that have spanned the 9-year-old child’s entire life. The couple has been embroiled in a custody fight for nearly as long.

A large number of people reporting concerns of abuse does not prove it occurred. But in the aggregate, research indicates a higher number of prior reports of child abuse correlates with an increased likelihood that an investigative finding of abuse will be supported. Tamara Fuller, director of the Children and Family Research Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who studies child protective services, said the number of prior reports is one of the best predictors that state investigators will find abuse took place.

Yet in this case, the more reports streamed in, the less state investigators seemed to believe that Bruce was harming his son. In fact, the cascade of reports shifted suspicions to the boy’s mother, Christine.

A spokesperson for DHS said the agency does not comment on its handling of specific cases.

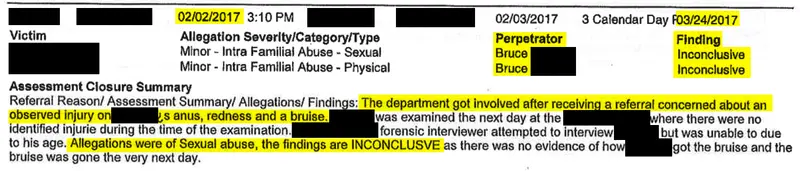

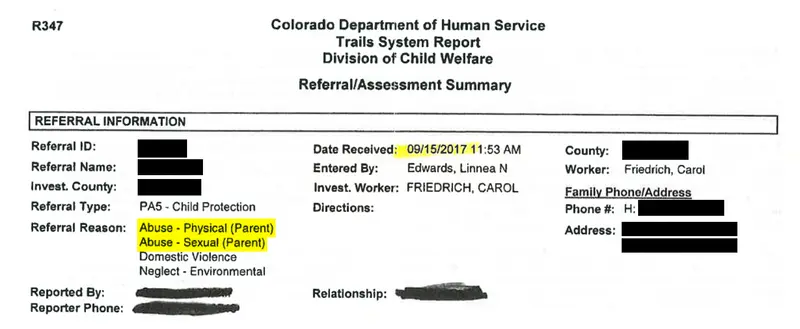

The reports were detailed and consistent over the course of years. In February 2017, a physician’s assistant at a local medical center reported that the child, then almost 3, had returned from spending time with Bruce with unusual bruising around his rectum. The report prompted an investigation that was closed a month later as “inconclusive” because there was no evidence to show how the child got the bruising, according to child welfare records.

In May 2018, the child’s clinical psychologist reported the boy had told her that his father hit him with a stick and that “dad touches his junk while he touches my penis.” (The psychologist noted to me that the child’s use of sexualized terms was indicative of an adult influence.) In July 2018, a pediatric psychiatry specialist reported that the child had told his mother and medical staff that he had been sexually abused. DHS declined to investigate the reports.

Would hearing these allegations have changed Coykendall’s assessment of Bruce and whether the child was safe in his care, I asked.

“Oh, absolutely,” she said.

“I know at the time, I did the best I could. … Did I miss something? Probably. Do we all miss something? Almost always. I think anybody who tells you they don’t miss anything is full of crap,” Coykendall said. “Maybe I missed something. Maybe I misinterpreted this.”

Allegations of Abuse Countered by Allegations of Alienation

The custody case playing out in a small town nestled in the mountains of southwest Colorado is a war of narratives.

Christine, backed up by more than a dozen mandatory reporters, two court-appointed custody evaluators and the child himself, alleges the boy’s documented injuries indicate he is being seriously harmed by his father.

Bruce, supported by another custody evaluator, law enforcement, child protective services and several court officials, maintains the boy’s injuries are the result of a normal, active childhood. Instead, he argues, the child is a victim not of physical or sexual abuse but parental alienation, a disputed psychological theory in which one parent is accused of brainwashing a child to turn them against the other parent.

The theory arose in the 1970s and ’80s, during a paradigm shift in U.S. family courts. As women entered the workforce in larger numbers and men played a bigger role in child-rearing, the assumption that women should be favored with custody in divorce proceedings was challenged. A “father’s rights” movement demanded gender-neutral custody proceedings, and, by the 1980s, most states began implementing joint custody after divorce. Courts were overwhelmed by custody battles, and judges began looking for experts to help them resolve high-conflict cases, particularly those involving allegations of abuse. They were a ready audience for Richard Gardner, a psychiatrist and the architect of parental alienation syndrome, the antecedent to parental alienation. Gardner theorized that mothers were brainwashing children against fathers in order to gain custody. The solution, Gardner said in writings and speeches, was to remove children from their mothers and employ “authoritarian” therapeutic methods, including “threat therapy,” to disabuse children of their supposedly false beliefs.

Today, parental alienation has still not been accepted as a mental health disorder by psychiatry’s diagnostic bodies. It has been denounced by the World Health Organization and shunned by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges for failing to meet court evidentiary standards. In May, a special reportreleased by the United Nations’ Human Rights Council blasted parental alienation as a “pseudo-concept” and recommended prohibiting its use in family courts.

According to court records, Bruce began accusing Christine of parental alienation in early 2016, after she filed for divorce and the judge was preparing to rule on their custody arrangement.

Today, parental alienation has still not been accepted as a mental health disorder by psychiatry’s diagnostic bodies.

They both describe their marriage as the result of an attraction of opposites.

Christine, a financial trust examiner for the state of Colorado, attended Penn State on a full athletic scholarship and later earned an MBA. She trained to be on the U.S. Olympic field hockey team until an injury ended her career. Last summer, mounting attorneys fees caused her to file for bankruptcy, she said.

Bruce dropped out of several colleges to pursue a range of jobs — ski instructor, boat builder, tow-truck driver and said he has operated several small businesses. Bruce speaks openly about struggling with alcoholism, starting in junior high school, but said he has been sober since shortly after becoming a father. Today, he works in theater production as a contract artist and set designer.

The two met in 2006 playing ice hockey and married three years later. Despite tensions in the relationship, they decided to have a child. After several rounds of in vitro fertilization, their son arrived in 2014.

The couple’s interactions soon escalated into what Christine describes as a pattern of violence against her and the infant. Christine moved out, and she and Bruce began alternating parenting time.

Bruce denies ever acting violently toward Christine or their son.

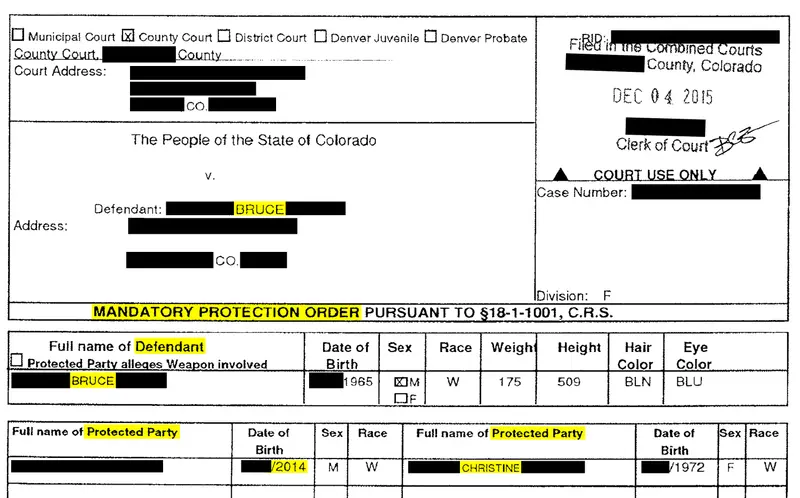

One weekend, when Bruce did not return their son to Christine, the couple clashed. He was arrested and charged with harassment and domestic violence for allegedly pushing her to the ground while she held their infant, according to police reports. Judge Donald Cory Jackson, who would later preside over the couple’s custody case, signed a restraining order prohibiting Bruce from having contact with his wife and son. Shortly after the incident, Christine filed for divorce.

Bruce was arrested a few weeks later for violating the order and spent the night in jail. In January 2016, he was convicted of domestic violence and harassment. Bruce took an Alford plea, a guilty plea in which the defendant does not admit to committing the crime.

Bruce says this is when Christine began fabricating the narrative she would spin for years that he is abusive and a threat to their son. “It was her initial sabotage: I never shoved her. Her and her mother concocted a lie to tell the police so that I would get arrested, so that they would have that first victory in the divorce case,” he said.

A year later, Bruce was arrested again and charged with stalking and domestic violence for capturing video of Christine and the child from his car, according to police reports. (The charges were later dismissed.) “If you saw that kid you would want to take him too,” Bruce told the police officer, according to the report.

Christine provided police with a timeline of 26 incidents from the past two years in which she alleged Bruce assaulted, harassed, recorded and stalked her. “Every time I leave my house I am afraid,” she wrote in a statement to police. “When he appears out of nowhere, and then disappears, I am shaking.”

Bruce said he recorded her in self defense and that their encounters were inevitable in a small town. “They were looking for any excuse to get me to look like I was the bad guy,” he said.

As Bruce argued this in court, the state Supreme Court ruled in another divorce case that parental alienation should be treated as a form of child endangerment. Advocates who want courts to consider parental alienation as a mental disorder view the Colorado ruling as an essential step toward establishing its legitimacy. As of now, the American Psychiatric Association does not include parental alienation in its diagnostic manual, the DSM-V. But the ruling, experts say, put Bruce’s allegations of alienation against Christine on equal legal footing with the claims of abuse against him.

“Is Mom Making This Up?”

At the beginning of the custody battle, the court was convinced that Bruce posed a physical danger to his almost 2-year-old boy. In the first permanent custody orders, Judge David Westfall found a “preponderance of evidence” indicated Bruce had committed domestic violence against Christine and was a threat to the child. He cited injuries the boy sustained while in Bruce’s care, including bruises to his head and an injury to his leg that left the toddler “unable to walk,” according to court documents. The judge also found that Bruce had failed to “properly” feed the child and had neglected his medical needs.

Westfall restricted Bruce’s parenting time in accordance with Colorado law, which requires the court to consider incidents of domestic violence when determining custody arrangements. He awarded Christine primary custody and sole decision-making authority over their son. Bruce maintained visitations with restrictions, including not being permitted to bathe the child. But the flow of reports with concerns that the child was being harmed while in his father’s care did not stop. The professionals making those reports to DHS and law enforcement worked at different institutions and lived in different parts of the state, some hundreds of miles from each other.

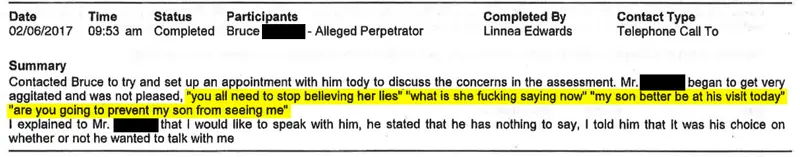

Bruce continued to rebut them, reiterating to child welfare investigators that his ex-wife was framing him to gain the upper hand in their custody battle. “You all need to stop believing her lies,” Bruce told investigators after the physician’s assistant reported in 2017 that the child had unusual irritation and burst blood vessels around his rectum after spending time with him.

Bruce said he began reaching out to parental alienation experts to advise him on his situation, which he feared was becoming dire. He also called DHS to accuse Christine of falsely reporting abuse.

As the child grew, his descriptions of abuse became more detailed. Susannah Smith, a clinical psychologist who began seeing the boy in the spring of 2017 at the recommendation of child welfare officials, made seven reports detailing his claims of physical and sexual abuse by his father. The boy told Smith that Bruce “hits me” and “pushes his ‘package’ against me,” according to the therapist’s reports.

But DHS caseworkers grew dubious of the allegations and increasingly convinced of Bruce’s explanation for the child’s disturbing statements.

Christine began to fear that the reports, intended to raise alarms about the safety of the child, were having the opposite effect.

Coykendall said this was likely the result of confirmation bias, the cognitive tendency to favor information that supports a predetermined conclusion and discard conflicting evidence. “Most DHS workers are loath to give credence to evidence when it goes against their intuitive feeling about a case,” Coykendall said. “Anecdotal ideas that the person is just a good ol’ boy can override concern that there’s something going down that’s not above board.”

Christine began to fear that the reports, intended to raise alarms about the safety of the child, were having the opposite effect.

It struck me that the response might have been different had it not played out in a town of about 2,500. Several of the investigators knew Bruce personally. He told me that Thomas, the child welfare official, attended his personal therapy session while she was investigating him for child abuse to understand more about his assault of a child when he was a teenager.

(Thomas denied that she attended a therapy session with Bruce. She said she interviewed him about the “incidents that occurred when he was a teen” as part of her child welfare investigation.)

Bruce also said he was revered by parents whose children performed in the school productions for which he designed stage sets. (Thomas was one of them, he said.) “The only potential grace that I might have gotten in this town is that I built, like, 100 sets for children’s theater,” Bruce said. “So a lot of parents in that town think I’m, like, a hero or whatever.”

Norman Squier, one of the first police officers to investigate Bruce for child abuse eight years ago, told me he and Bruce had acted together in local theater productions. Squier said he also knew Christine, but that his familiarity with both of them did not influence his investigation. He did tell me that he believed Bruce would provide a “great home” for the child and that he thought Christine’s “anxiety” caused the child harm.

“Is mom making this up? What might her motive be?” a DHS caseworker wrote in February 2017, following a report from a victim’s advocate that the child had told his mother “he touched my fanny and it hurt.” Child welfare officials did not investigate further.

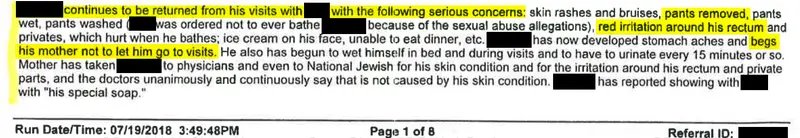

“Is mom creating parental alienation with regards to dad?” the same caseworker wrote in September 2017, after Smith reported that the toddler had returned from visiting Bruce with “skin rashes and bruises, pants removed, pants wet” and “red irritation around his rectum and privates, which hurt when he bathes.” The case was closed with no findings of abuse against Bruce.

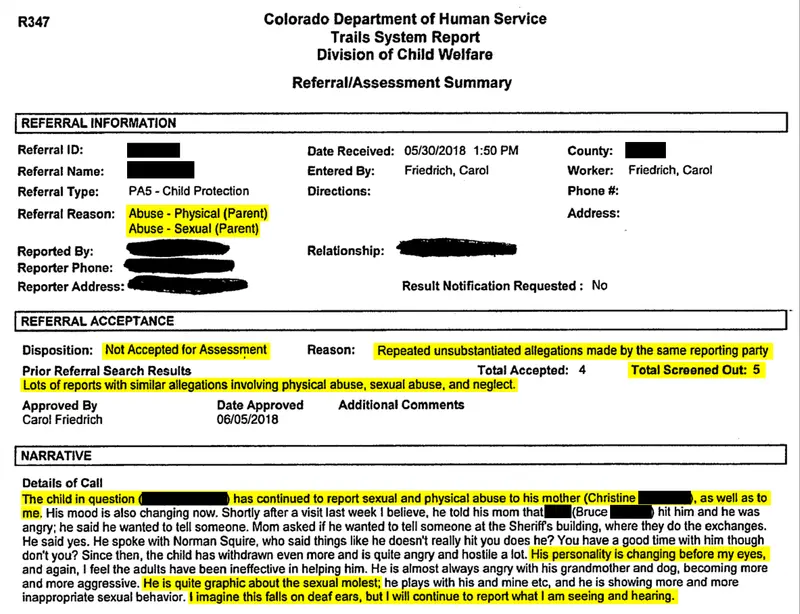

The agency began declining to investigate reports about the child from Smith and other mandatory reporters.

“The child in question has continued to report sexual and physical abuse. … He is quite graphic about the sexual molest,” Smith wrote to child welfare officials in May 2018. “I imagine this falls on deaf ears, but I will continue to report what I am seeing and hearing.”

I asked Smith what she thought of the argument, reflected in DHS’ response to her reports, that Christine was influencing her son to claim abuse in order to alienate him from Bruce.

“These complaints aren’t coming from Christine — she’s scared to open her mouth. They were coming from” the child, Smith told me. “And, like I said in some of my reports, it’s extremely rare that you get not only the physical evidence, which was reported by multiple physicians, but you also get his talking about it.”

“Anyone who is quicker to believe that myself and a dozen other professionals were hoodwinked into reporting child abuse, rather than that a child’s outcry needs to be heard and investigated, is willfully turning a blind eye,” Smith said.

Like I said in some of my reports, it’s extremely rare that you get not only the physical evidence…

…which was reported by multiple physicians, but you also get his talking about it.

Susannah Smith

Clinical psychologist

Speaking to Dreyfus

Elizabeth Gyorkos, a physician’s assistant who had treated the child for years for allergies, reported to DHS that the boy had returned home from visits with his father with unusual redness and swelling around his anal area and genitals.

Gyorkos told me she remembered the case clearly. “He was sitting quietly in the exam room. When the doctor, who is a big man, came in to see him, [the child] shrank in his chair and cupped both of his small hands right over his crotch, like he was trying to protect himself.” When I told her that her report to DHS had been dismissed, she became distressed. “Nothing happened?” she said. “What is it going to take for these people to see what’s going on? Even then, I remember thinking to myself, and I think I even told my husband, ‘This is the case you will hear about one day.’”

I asked her if she recalled anything about how Christine behaved around the boy. Did she ask him leading questions? Did she say negative things about the father?

“No,” Gyorkos said. “She was just a concerned mom trying to do the best she could to protect her child.”

Child welfare agents did not accept the report from Gyorkos and did not investigate further. “The consensus is that this referral is based in custody issues,” the June 2018 DHS report states.

“There is a larger concern focusing on” the mother “and her inappropriate victimization of the child.”

In the fall of 2018, four mandatory reporters called DHS during the child’s first week of preschool saying he had told them that his father “hurts him” and “fools around” with his private parts. After this, DHS ran out of patience, Bruce said. “I was told that they were so sick of all these dozens of calls to DHS that they turned my case into a Dependency and Neglect to bring in as much, like, firepower to put an end to this that they could.”

Child welfare agents opened an investigation into both parents, accusing Christine of emotionally abusing her son. The basis for the claim: photographs she had taken of the boy’s genitals in order to consult with doctors about his injuries, according to child welfare records. The case was dismissed several months later with no findings of abuse, though the agency did require Bruce’s parenting time to be supervised.

But the investigation confirmed her fears, Christine said: Child welfare agents believed Bruce’s narrative that she was manipulating not only her child, but also the professionals who were continuing to report abuse. “It became clear to me at that point that I was being targeted, and that I had no power to defend myself,” Christine told me. “It didn’t matter that I wasn’t the one making the reports. They would boomerang back at me.”

Christine in Her Own Words

Going to Police

Frustrated by DHS’ disregard for their reports, a handful of the mandatory reporters took their concerns directly to the police.

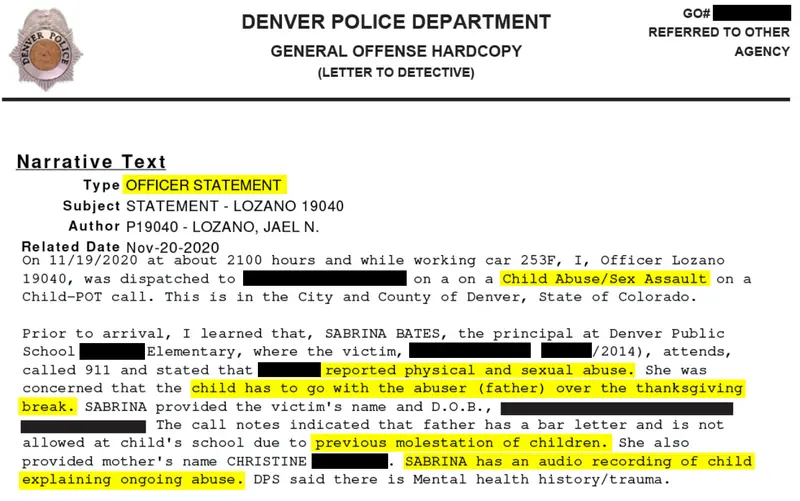

On Nov. 19, 2020, police responded to a 911 call from Sabrina Bates, a Denver elementary school principal. According to police reports, Bates had a recording of a first grader saying that his father touches his penis and hits him. The child was Bruce and Christine’s son. Bates told police she had received the recording from the child’s mother; Christine told me she had not gone to police or child welfare officials directly because she feared that if she reported it would be used against her.

Christine had moved to Denver the previous year to care for her elderly mother and the child, now 6, was spending weekends and some holidays with Bruce. Bates’ call to Denver police came after reporting concerns to DHS for months with no apparent result. “I’ve been in education for 16 years, and I’ve never seen a child as traumatized as [this child] was and continues to be. … There’s not a damn thing being done,” Bates told me.

The report was referred to the rural sheriff’s office in the jurisdiction where the abuse was alleged to have occurred. That’s where the investigation stopped.

I’ve been in education for 16 years, and I’ve never seen a child as traumatized…

…as [this child] was and continues to be.

Sabrina Bates

Elementary school principal

Speaking to Dreyfus

A representative confirmed the sheriff’s office received a referral from Denver police, but no investigation was opened. The likely reason, according to the representative: The officer knew about the case and had previously deemed the allegations unfounded.

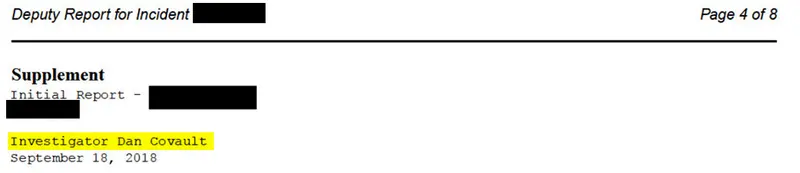

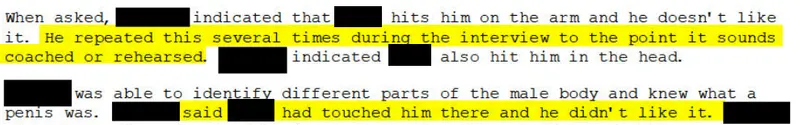

The sheriff’s office had been investigating the case for years. In 2018, a DHS caseworker contacted the sheriff’s office after receiving a slew of reports from mandatory reporters describing harm to the child. According to a police report, the caseworker spoke to Officer Dan Covault and initially described the situation as Christine “making allegations that [the father] is sexually assaulting” the child even though none of the reports had come from Christine. Covault interviewed the child alongside two DHS caseworkers. They said the boy had told them that he had been sexually and physically abused by his father. “[The child] was able to identify different parts of the male body and knew what a penis was,” Covault wrote in a police report describing the interview. The child said that his father “had touched him there and he didn’t like it.”

But after consulting with the DHS caseworkers, Covault discounted the child’s account because it seemed the boy had been coached. While the child claimed Bruce touched his penis, “he had trouble remembering where and when this happened,” Covault wrote in the report. “His answers appeared to be fabricated. His responses to being touched came easily to him as if he had been coached.”

Coaching is a term that frequently appears in literature about parental alienation to connote one parent training a child to believe and report false claims about the other parent, including claims of abuse. The mental health experts I spoke to, including the boy’s therapist and several medical professionals, recalled the child being detailed and consistent in his accounts of abuse. Neither of the court-appointed psychologists who had evaluated the case at the time voiced concerns that Christine was coaching the child. Still, Covault was swayed by what the DHS caseworkers told him: All of the mandatory reports could be traced back to Christine and her efforts to keep primary custody of her son.

In explaining the child’s statements, the officer’s report echoed Bruce’s claims of alienation. “It appears [the mother] is making unsubstantiated reports. It’s possible she is doing this because there is another custody hearing in December,” Covault concluded in his Sept. 18, 2018, report. “Nothing further at this time.”

(Sheriff’s officials didn’t close the case until this past January, immediately after I filed a public records request seeking the investigative report. The report said Covault closed the case because neither Christine nor the mandatory reporters had responded to attempts to gather more information. My records request did not produce any emails from Covault to Christine or the mandatory reporters.)

Covault declined to speak with me.

Another police officer investigated the same allegations but reached a different conclusion. The marshall of a nearby county asked police officer Monty English to take a second look at the case because of the seriousness of the claims. English, who has since retired, said he spoke to several of the doctors who were mandatory reporters and reviewed photographs of injuries the child had sustained while in his father’s care. “I think they had more than enough to charge him with at least child abuse,” said English, who told me he worked on sex assault investigations for over a decade. “I was disturbed by the fact that they had all these allegations and it didn’t seem like anyone was following through or documenting the facts. … You just don’t turn your back on that kind of stuff.”

English said he spoke with the detective investigating the case. When he voiced his concerns about the child’s situation, he said he was told that the child’s mother was “crazy.” “They said if she comes back we’re going to charge her with false reporting.”

“Significant Evidence That Remains Unanswered”

The alienation argument and the doubts it raised about the abuse allegations made their way into the courtroom. Judge Donald Cory Jackson had been appointed to the case, and in January 2020 he was preparing to issue a new custody ruling. He was not swayed by a custody evaluator’s deep concerns that Bruce posed a threat to the child.

Bruce Bishop, a Denver-based clinical psychologist, was the second custody evaluator to work on the case. Evaluators like Bishop, referred to as “parental responsibility evaluators,” function as privately funded alternatives to court-furnished evaluators. Colorado courts opened their doors to these specialists more than a decade ago to allow a broader range of psychologists to lend expertise to custody decisions.

Bishop advised Jackson that “a continuation of the current parenting time plan constitutes a significant emotional and physical risk to this child” and recommended against unsupervised visits with Bruce. He expressed concern that DHS agents’ “pre-existing relationships with father” could have “tainted” their investigations. “I hope the possibility that the child has been sexually abused is false, and it probably is,” Bishop wrote. “But nevertheless there is some significant evidence that remains unanswered — and a ‘miss’ on this would have catastrophic consequences for the child.”

But Jackson’s ruling stated that the “persuasive issue” was not the child’s injuries or reports of abuse but rather “each parent’s attitude toward the other.” He increased Bruce’s visitation time from two supervised visits a week to unsupervised weekends twice a month, summers and holidays.

Bishop would not comment on the case specifically, but he told me it is rare for a judge to disregard his recommendations, especially when they pertain to the physical safety of a child. “There’s no remedy if I see a report used in a way that I think is irresponsible or naive,” he said.

After two years, Bruce asked the court for more parenting time and sought yet another professional to review the custody arrangement and advise the court. While it is common for parties to list several options when requesting a custody evaluator, according to experts and Colorado parents, Bruce named only one: Edward C. Budd. (In an interview, Bruce denied requesting Budd, though court documents show he did.)

I have a pretty good people sense. I’m not very often wrong about…

…not fundamentally wrong about — people very often.

Edward C. Budd

Parental responsibility evaluator

Speaking to Dreyfus

Christine objected in court to Budd being appointed. She saw no need for a new evaluation — Bishop’s report was less than two years old. But unlike other states, where both parties must agree on a custody evaluator or, if they cannot agree, a judge chooses one, Colorado law permits courts to appoint an evaluator over the objections of one of the parties to a case. Bruce said he paid $17,000 for the new evaluation, including Budd’s travel fees.

Budd, 68, who holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Texas Tech University, began working as a custody evaluator in Colorado in the late 1980s. He has since been involved in about 675 cases, he said. He is tall, walks quickly and doesn’t make small talk. “I have a little tolerance for boredom,” he told me when we met, leaning back in his chair at his suburban Denver office and popping a cough drop.

He chose to become a custody evaluator because the job made excellent use of his “gifts,” including an ability to sift through large amounts of “wasteful” information and “zero in on the key issues.” In his report on Bruce and Christine’s case, he referred to this as “separating the wheat from the chaff.” He told me, “I’m not very often wrong about — not fundamentally wrong about — people.”

Budd sometimes gives parents a self-authored document that outlines the evaluation process using hypothetical parents, John and Mary Doe, and their 8-year-old son, Justin. Mary claims that John is physically and emotionally abusive to their son. John claims that Mary is “mentally-ill.” John remains involved in his son’s life despite mom’s campaign of “alienation.” The handout asks parents to “Imagine that you’re the evaluator, responsible for fostering Justin’s well being… The point: it ain’t simple, folks.”

His psychological test of choice is the Rorschach — a widely criticized method of analysis in which subjects interpret inkblots. (In 1999, several psychologists called for a moratorium on its use, citing the test’s incompatibility with the APA’s standards.) Unmoved by “hostile” skeptics, he said, “It’s a non-fakeable test.”

ProPublica found that Budd has been the subject of multiple complaints to the Colorado State Board of Psychologist Examiners in recent years and is currently being investigated by the panel. Most of the complaints against Budd have been dismissed and none has resulted in disciplinary action against him. One complaint that is still under investigation originated with Christine, who alleged that Budd failed to seriously consider claims of abuse in her case. According to Budd’s notes, it does not appear he interviewed any of the mandatory reporters who voiced concerns that the child was being abused.

Budd knows parents are complaining. “Everyone’s pissed about everything, all the time,” he said, quoting a comedian and laughing. He referred to the complaints as “just an annoyance.”

“I’m going to say something that is gonna sound self-aggrandizing, but I think if you thought about it carefully it really isn’t,” he said. “If people would take the report and go, ‘OK, we’re going to use an expert. We’re going to do what he told us,’ I guarantee you their kids would be better off. They don’t do that.”

“How Do You Tell When Someone’s Lying?”

Christine met Budd last year, on a Monday evening in mid-March. She had taken off the week from work to prepare. She had scanned her bookshelves and hidden certain titles — “Mothers on Trial,” by Phyllis Chesler; “Fifty Feminist Mantras,” by Amelia Hruba. She purchased a formal dining room table and set it with folded napkins and the knives facing inward.

A home-cooked meal was ready at 5 p.m. Budd arrived late, blaming his GPS. “What are we having?” he asked upon arrival. The next hour and half was spent in stilted conversation. The visit concluded after Budd received a tour of the home, and the child escorted him out.

Two days later, Christine met with Budd at his office.

Budd started the 45-minute interview by asking what had attracted her to Bruce and for details about her job. Then the interview shifted to rapid-fire questions captured in Budd’s notes and a recording, which Christine shared with ProPublica.

“[Bruce] says he often finds that he encounters people that are involved with [your son] that you’ve already told ’em horror stories about [Bruce]. … You’ve kind of set up the situation by telling them about him. Is that accurate?”

“No,” Christine said.

“You ever told anybody anything that might give them reason to be negatively predisposed towards him?” Budd asked.

“When I’ve ever met with therapists I have always requested that they speak with the previous therapist to get their information,” she responded.

“Ever tell a health care provider that he’s a pedophile?” Budd pressed.

“A health care provider? Well, health care providers typically have all the court orders —”

“It’s a yes or no question,” Budd said, cutting her off.

“I don’t recall,” Christine said. “But I have provided every health care provider with court orders so they can understand the situation.”

“Well for the moment, that’s all of my questions,” said Budd, bringing the interview to an end. “No point repeating things you’ve already said to me but anything you haven’t told me I’m all ears.”

Christine sat in her parked car with her head on the steering wheel for a long time before driving home.

The following week, the custody evaluator visited Bruce at his home in the mountains. At Budd’s request, Bruce prepared spaghetti. “I guess he wanted to make sure I could cook,” Bruce said.

In the interview, which lasted an hour and a half, Budd prodded him about his behavior.

“Is it possible that you sometimes behave in a way other people find offensive and don’t really recognize?” Budd asked, according to his notes of the meeting.

Bruce appeared to cut him off. “I think disagreeing with people, yeah, maybe someone gets offended by that. … I’m sorry they get offended but …”

“So it’s their fault if they get offended?” Budd asked.

“How they choose to react and behave, that’s their choice, they chose to completely ignore my perspective on that matter. … She refused to consider that … my son has not been abused by me and everyone’s running around like he has.”

Budd asked why his son had been repeatedly injured while under his care. Bruce explained he was redoing the bathroom when the boy got an arm injury in 2018; the two had been “playing a game” when his son reported to his therapist that his father had squirted him in the face with a hose and while running to get away had fallen on a metal fence.

Bruce also recounted his sexual assault of the 4-year-old girl when he was 16. “Budd barely even batted an eye,” Bruce said.

“How do you tell when someone’s lying?” Bruce asked him. “There are two different stories being told. They can’t both be true.”

Budd avoided answering the question.

The Hearing

On Sept. 23, Bruce and his lawyers arrived at the rural courthouse. They huddled, glancing occasionally at the empty opposing counsel’s table and the double-doors leading into the courtroom.

Budd’s April report had described Christine’s behavior as “destructive,” “irrational” and “pathological” and recommended that she lose primary custody of her son. A day after Budd issued the report, Christine’s attorney informed her that she would no longer represent her because there was no realistic path to winning the case. “There is no fighting chance,” she wrote in an email to Christine.

Since then, Christine has represented herself in the district court case. She filed a motion asking for the hearing to be paused, citing medical reasons. It was accompanied by a doctor’s note recommending she not participate because of a serious medical condition. Christine told me she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the events of the past eight years. She described her experience in family court like being “put on a stick … and just tortured,” adding: “Your hands are tied behind your back. And then you look over, and the same thing is happening to your child. And then a group of 10 people would come in with notepads and take notes on how you’re handling the torture.”

Jackson denied her request to pause the hearing, saying the health issues were not “specific.”

Christine didn’t attend the hearing. She was in London with her son, fearing it might be her last opportunity to travel with him, she told me.

It was like you were put on a stick. And people came up and just tortured you in whatever way that they could find. And your hands are tied behind your back. And then you look over, and the same thing is happening to your child. And then a group of 10 people would come in with notepads and take notes on how you’re handling the torture.

That’s what I felt like family court — or I feel like — family court is. We’re not judged upon our acts within our daily lives. We’re judged upon how we receive this consistent severe trauma on a daily basis for leaving a man.

Christine

Mother

Speaking to Dreyfus

Other than Bruce himself, Budd was the only witness in court. He testified remotely, his face looming on a large screen angled toward the judge. Budd served as both an evaluator for the court and as an expert witness for Bruce, according to court documents. Bruce told me he paid him $1,600 to appear on his behalf.

Colorado law requires custody evaluators to advocate for the child’s best interest. But the court can allow an evaluator to act as an expert witness for one side if the judge deems them qualified. Experts said these two roles are in conflict and that the same person attempting to do both is a breach of the American Psychological Association’s guidelines, which instruct evaluators to strive for impartiality.

Though Budd would not comment on this case specifically, he said in a written statement that “my only role … is to act on behalf of the child” and any implication that he served in a “dual role” is “utterly inaccurate.”

When Bruce’s attorney asked Budd what led him to conclude there was no credible evidence that Bruce abused his son, Budd responded that the “statement’s kind of self-evident, there’s no evidence for it. Those allegations have come largely from statements by [the child]. And, apart from those statements, there is no evidence: No eyewitness accounts, no findings from medical exams, no findings from evaluations of the child.” The source of the boys’ allegations were Christine’s “delusional” beliefs about Bruce, Budd explained. Professionals who spoke to Christine were similarly compelled to believe Bruce was harming the child, he said. But professionals who interacted with Bruce or observed him with the child were more likely to see that he posed no threat to his son.

“Christine goes out of her way to portray [Bruce] as a dangerous man and an abusive and incompetent parent,” Budd had written in his report. “By the time [he] talks to an educator, physician, or therapist, that person may have been told he is a violent spouse abuser and child molestor.”

“[The child] is not some sociopathic little person who just likes to lie — he’s confused about what’s actually happening,” Budd told the judge. By joining his mother in her “delusional” beliefs, the child has lost the ability to differentiate between “what’s real and what isn’t real.”

Jackson listened to Budd’s analysis and did not ask any questions.

Budd has cited parental alienation by name in the past, but did not use the term in his report or testimony. He told me last summer that “alienation” has become so divisive that he prefers “pathological alignment” to describe family estrangement caused by one parent. Still, Budd’s analysis of the case placed him squarely alongside state investigators, police officers and court officials who had decided that it was Christine and not Bruce who was responsible for the child’s allegations of abuse.

For almost two years, I had interviewed dozens of individuals to uncover a set of facts that would either prove or disprove Bruce and Christine’s divergent stories. But what I found instead was the same set of facts with two vastly different interpretations. Christine and Bruce pointed to the same police reports, child welfare records and statements from their son to bolster wildly different conclusions: abuse or alienation.

Years ago, Coykendall was swayed by the first interpretation: that the reports of abuse were evidence of a hapless but well-meaning father, floundering under the scrutiny of an overcritical mother. But years of unabating allegations against Bruce had caused her to second-guess that interpretation. “It’s my training as a scientist practitioner,” she told me. “I have to retest hypotheses, even when it means admitting I was wrong.”

Budd’s conclusion that this was by definition a case of alienation, not abuse, seemed to decide the issue for the court. Though Colorado law requires judgesto consider incidents of domestic violence when determining custody arrangements, Jackson did not mention Bruce’s 2016 domestic violence conviction during the hearing or in subsequent orders. Jackson found Christine to be a danger to the boy’s physical and emotional health and ordered the child to be relocated to his father’s home “immediately.” Christine said she and her son cut short their trip and rushed back from London to comply with the order.

A spokesperson for the court said Jackson would not comment on the case.

The following day at 8 p.m., in the deserted parking lot of a bagel shop, the 8-year-old boy rested his forehead against his mother’s, who knelt on the pavement, for a moment. He dragged a robot duffel bag packed with some of his favorite shirts, pajamas and a fox stuffed animal.

“If I Don’t Pretend He’ll Get Really, Really, Really … Mad”

Bruce has had primary custody and decision-making authority for his son for nearly a year.

Christine sees the child on the first and third weekend of each month and for two weeks during the summer, though not this year because she missed an April 1 deadline to notify Bruce of which two weeks she wanted, as stipulated in the court order.

Now represented pro bono through the Colorado Bar Association, Christine has appealed Jackson’s custody ruling.

“It’s the next step in the playbook of fucking with the courts to get your way,” Bruce said of the appeal. “Unfortunately, I have to think like a liar to fight a liar.”

Over the last two years, reports by professionals who suspect the child is being harmed have slowed, according to DHS records. Budd was one of the last professionals to document hearing the boy say that his father hurts him, according to notes from the custody evaluator’s interview with the child. It is unclear if Budd, who is legally mandated to report suspected harm to a child, told officials about the child’s claim. DHS records indicate he did not. Budd said in a statement that he is unable to discuss specific cases without permission or a court order.

Christine said she believes the boy has stopped talking about the abuse because they both have learned the consequences of speaking up. She sent me recordings of the child from the summer of 2021. In one, the child, after getting off a phone call with Bruce, tells his mother between sobs that “he thinks I’m telling lies.” In another, he says that he acts happy at his dad’s house because “if I don’t pretend he’ll get really, really, really … mad.”

The recordings were made the same summer Bruce filed a motion, granted by Jackson, to prohibit the boy’s new psychologist from testifying in court. The child psychologist, a trauma specialist, had made seven reports of suspected physical and sexual abuse to DHS between the summer of 2020 and spring of 2021 based on the child’s statements. (The psychologist declined to speak with me about the case, citing patient confidentiality.)

In the motion to prohibit the specialist from testifying, Bruce accused Christine of enlisting psychologists who “treat the child as if his statements are true, and reinforce the lies.”

Bruce told me he believes his son is at long last healing from years of severe parental alienation. “My son is finally starting to act like a normal kid,” he said. But Bruce also admitted his son has struggled with the adjustment. Late one night last fall, Bruce told me he was at his kitchen table doing paperwork when he heard his sleeping son call out for his mom. “I just went in and sat next to him for a second and touched his arm, but he didn’t wake up. He was just having a dream,” Bruce said. In a “perfect world,” he would like to co-parent, Bruce said, so his son doesn’t feel torn between him and Christine. “He wants us both in his life. But goddammit, I’m not going to let him be in that situation where he’s being turned into this anxious little ball because mom thinks he’s being abused.”

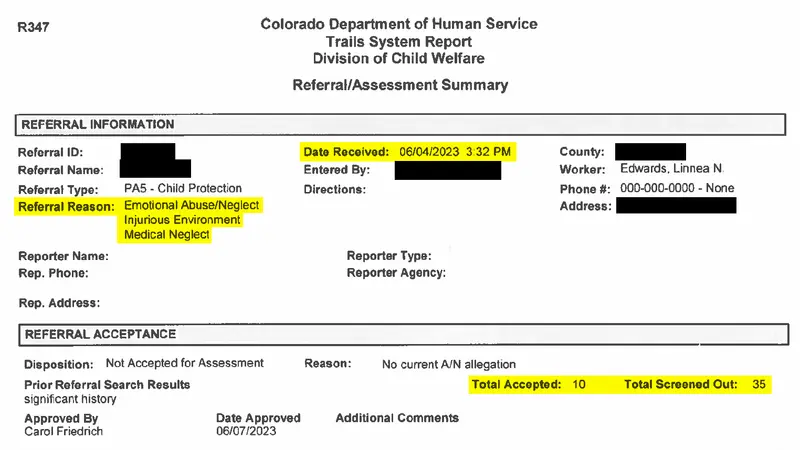

Though calls to DHS with concerns that Bruce is harming the child have slowed, they have not stopped. On June 4, the agency received a report from a psychiatrist that the child had sustained an abrasion on his back “the size of a nickel” while in Bruce’s care. The boy, who has always been skinny, appeared “malnourished,” according to the report. At almost 4 feet, 3 inches tall, he weighed 52 pounds.

The psychiatrist, who knows Christine personally, told me she contacted the agency after receiving a text message from Christine with a photo of the injury. Christine asked her not to make a report for fear it would be used against her, the psychiatrist said, but her legal responsibility as a mandatory reporter compelled her to do so.

Christine had texted me the same photo. The child’s hip bones protruded and individual vertebrae were visible. I also noticed the welt on the child’s back described in the DHS report.

I asked Christine if she knew how he got the injury. “I learned a long time ago to never ask him questions,” she texted back. Bringing him to a doctor would risk contempt of court charges and potential jail time for making medical decisions without Bruce’s permission. The court gave Bruce 100% medical decision-making authority over the child.

Bruce did not know about this most recent report until I called him in July. He said his son sustained the back abrasion “because he kind of ran into the butt end of a hockey stick.”

“He’s a 9-year-old boy. That stuff happens all the time,” he said. He saw no need to take him to a doctor to treat the injury. That would be “making a mountain of a molehill.”

And what did he make of the claim that his son appeared malnourished, I asked.

“He might look skinnier because he’s stretching,” Bruce said. “But he’s eating fine.”

When I told Bruce the number of reports that had now been made against him, including this most recent call, he referred to a joke he had made about taking home a medal. “We’re getting up there to take first place,” he said.

The agency did not investigate the report, which joined 35 others that had been screened out without further scrutiny.

Editor’s note: This story is based on public, court and child welfare documents and the accounts of more than 30 individuals connected to the eight-year custody case. Both parents had numerous on-the-record conversations with the reporter and were given the opportunity to be photographed and filmed for this story. We are only using the parents’ first names to protect the child’s identity and minimize the future impact of this reporting on him. For the same reason, we are pixelating certain images and redacting the child’s name in audio recordings. We recognize the identities of the parents and child will be obvious to many who know them. But we believe calling attention to the case offers an opportunity to understand the way in which accusations of parental alienation play out in custody cases.

Mariam Elba contributed research. Nadia Sussman and Shannon Mullane contributed reporting.

Illustrated portraits by Kate Copeland for ProPublica.

Photo editing by Andrea Wise and Jillian Kumagai.

Art direction by Anna Donlan and Andrea Wise.

Design and development by Anna Donlan.